Finding Voice, Form, and Feedback: Teaching Performance Composition as a Communication-Intensive Course

This is the second installment in our C-I in Action series where we follow along through the process of teaching a communication-intensive course. Last week, we introduced you to Communication Studies professor Dr. Naomi Bennett. This week, we look at some of the initial planning and the first few weeks of the course.

Maybe the third time’s the charm!

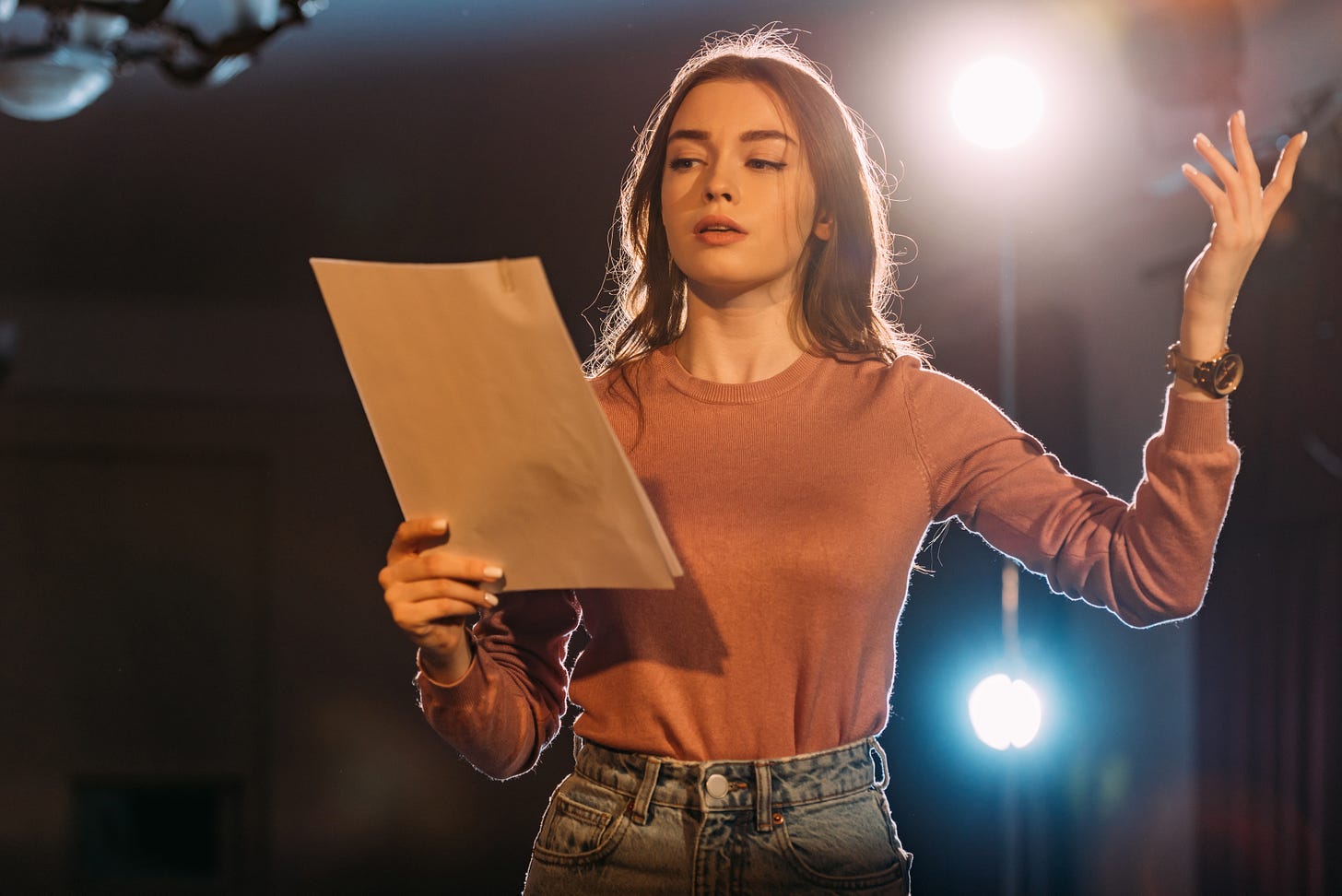

While this semester is not Naomi’s first time teaching the course, or the first time embedding communication-intensive approaches, in this third time to teach the class, Naomi has made some significant changes that reshape how communication is taught through performance. Performance Composition is an intermediate-level course in the Department of Communication Studies where students explore original performance as a form of communication, writing, staging, and presenting their own work. The course centers on three major projects: two solo performances and one final collaborative piece. Along the way, students develop skills in both written and spoken communication, with particular attention to poetic language, metaphor, thick description, and embodiment of text. But something was missing before, and so Naomi took on the task of redesigning how she taught the course.

Re-designing the Course—Literally and Figuratively

As we followed Naomi through the semester, she explained that the course reflects some changes, both in structure and pedagogical focus, to align more intentionally with principles from performance studies and communication pedagogy. Rather than organizing the course around specific poetic styles, Naomi decided to emphasize linguistic techniques—particularly metaphor and thick description—that students can apply across genres. The assignment sequence was also restructured: beginning with poetic performance and then moving into personal narrative, creating a throughline that allows each unit to build on the last.

The final project, originally a MyStory-style performance, using intertextuality to weave together personal, popular, and professional narratives, was also reimagined. The original format, while rich in theory, proved challenging in practice for the students. So this semester, the assignment was revised to focus solely on intertextuality: students now create a group performance that blends excerpts from their earlier solo work. It was hoped that this shift would allow for deeper exploration of connection while working within time constraints that spark creative decision-making.

“Intertextuality puts performance texts in communication with each other, allowing the performer (students in this case) to uncover meaning through that dialogic engagement. In integrating C-I pedagogy to this course, it was important to me that students be able to learn and practice this type of discipline-specific communication, which is one of the foundational methods used by performance scholars.”

Scaffolding Feedback and Process

A core goal of the course is helping students revise and grow through feedback. With performance-based work, this extends beyond written drafts to include physical and vocal choices, embodiment, and audience response. Naomi emphasizes transparency, explaining the purpose behind each assignment and workshop. This approach stems in part from earlier semesters where students resisted expectations they didn’t yet fully understand.

To support peer response, the course uses Liz Lerman’s Critical Response Process. While it takes time to learn, students quickly begin offering nuanced, supportive, and constructive feedback. To give every student space for revision, each student presented three drafts and received feedback each time. Even with weather-related schedule disruptions, Naomi found that protecting time for reflection and feedback is essential.

Sensory Foundations and Performative Writing

From the very first class, Naomi set the tone through sensory engagement. Rather than reading the syllabus, students began with a six-senses observation exercise (including proprioception). They described an object in rich, thick detail, sometimes turning their writing into riddles. This exercise introduces the idea of communicating embodied experience in playful yet profound ways.

Next, students observe a non-human living thing and respond through a written and physical piece using DT3 (Dance/Talk x3), a movement structure from InterPlay, a performance practice created by Cynthia Winton-Henry and Phil Porter. Many course activities draw from InterPlay as a way to bridge the textual and the physical—helping students build fully embodied performances. Even early in the semester, these efforts yield results: one student, observing a blade of grass, used their entire body—not just their arms—to show how it swayed in the breeze. That kind of full-body communication is a key goal of the class.

A Soundtrack to Story

In the second week of class, students responded to instrumental music—”Tamarack Pines” by George Winston—as a prompt for poetic writing. When students began this activity, their work leaned toward summary rather than sensation. With a little more time in a second round of writing, students focused on evoking feeling and their pieces transformed. They became richer with metaphor, image, and emotional depth. And this is when Naomi’s foundational goals for the course began to be realized. The course is really about helping students find their voices, their stories, and meaningful ways to communicate through both language and performance.

“My greatest joy as an educator is in watching each student discover their voice, discover what they are passionate about, and discover how to communicate and inspire that passion in others.”

Teaching Communication through Ambiguity and Embodiment

Perhaps one of the most important lessons students can take from this course is that communication isn’t always crystal clear—and that’s not a flaw, but a feature. There is ambiguity in communication and space for interpretation; both of these are an invitation to feel rather than simply understand. All of these are part of what gives performance its power.

Naomi hoped that by the end of the semester, students would leave not only with sharpened skills in writing and performance, but also with the ability to listen, reflect, revise, and collaborate. The class activities incorporate voice and movement, metaphor and memory, individual expression and group creation—students learn to communicate in layered, human ways. And ideally, they also learn something about themselves and each other in the process.

Read more from this C-I in Action series

Part 1: Meet Communication Studies Professor Dr. Naomi Bennett and learn a little about her Performance Composition C-I course

Part 2: Take a look at some of the initial planning and the first few weeks of the course

Part 3: Exploring the importance of feedback and a willingness to shift plans to ensure successful course outcomes

Part 4: Recognizing a need to change course to facilitate meaningful student engagement, and seeing the outcome of that revision to the plan

Part 5: Explore how scaffolding, trust, and feedback shaped the second half of the semester

Part 6: Students begin building confidence, critique, and connection by putting what they’ve learned into practice

Part 7: Students close the semester balancing challenge and care in the second round of personal narratives